I recently came across Randal Olson's excellent post on how the usage of sex, drugs, violence, and cursing in movies have changed over time. This article led me to start thinking: how else have movies changed over time? Has the content of movie taglines (such as "The park is open." for Jurassic World or "Some men dream the future. He built it." for The Aviator) changed over time? In particular, have movie taglines gotten more negative?

Getting a "sentiment score"

Tools and Data

The data for this analysis is freely available via IMDb's interfaces. I extracted all of the taglines along with each film's genre (using the taglines.list and genres.list files) into a pandas data frame. I used the excellent Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK) as a scaffolding for all of these analyses. To limit the analysis to only those movies with taglines in English, I used langdetect. Finally, I used the SentiWordNet 3.0 (SWN) database to get the actual scores for each word. The final analysis was performed on 7,381 taglines.

The problem of multiple meanings

One of the challenges of extracting sentiment I had underestimated before attempting this analysis is that words can have dramatically different connotations depending on their context. For example, "killing" might generally have a strong negative valence, but in the context of "killing it," might be positive. Moreover, each word is represented in the SWN database separately for each of its unique contextual meanings.

While I made rudimentary attempts to deal with this problem, I mostly ignored it because the absolute sentiment score of a given tagline is irrelevant in these analyses. All that matters here is the relative sentiment scores across years/genres, so, hopefully, noise due to multiple meanings should average out. That said, the multiple meanings problem is absolutely a confound in these analyses.

Putting it together

The first step in my sentiment analysis pipeline was to tokenize each tagline into individual words and punctuation marks. I tagged each token with its part of speech, and excluded punctuation marks, articles, etc., keeping only nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs. Each remaining word in a tagline was then compared to the SWN database to extract each word's net sentiment score. Because each word returns multiple results in the database (due to different parts of speech and different definitions), I filtered the matches to only include database entries with the same part of speech as my requested word, and took the difference between the average positive score and the average negative score as each word's net sentiment score. To get a final sentiment score for a tagline, I simply summed each component word's net sentiment score.

Because sentiment scores are represented as the difference between positive and negative, a value of 0 indicates a neutral connotation, and positive/negative values represent positive/negative valence.

Results

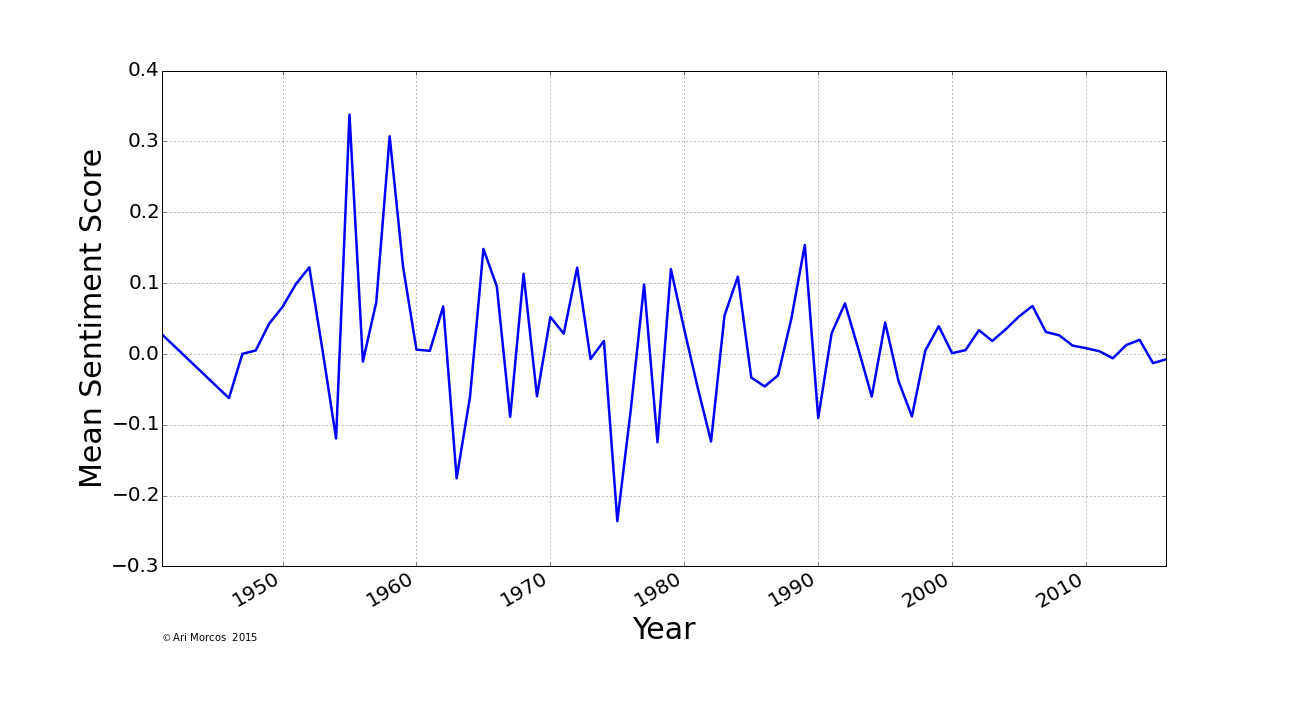

So, what happened? Have taglines gotten more negative over the last 50 years?

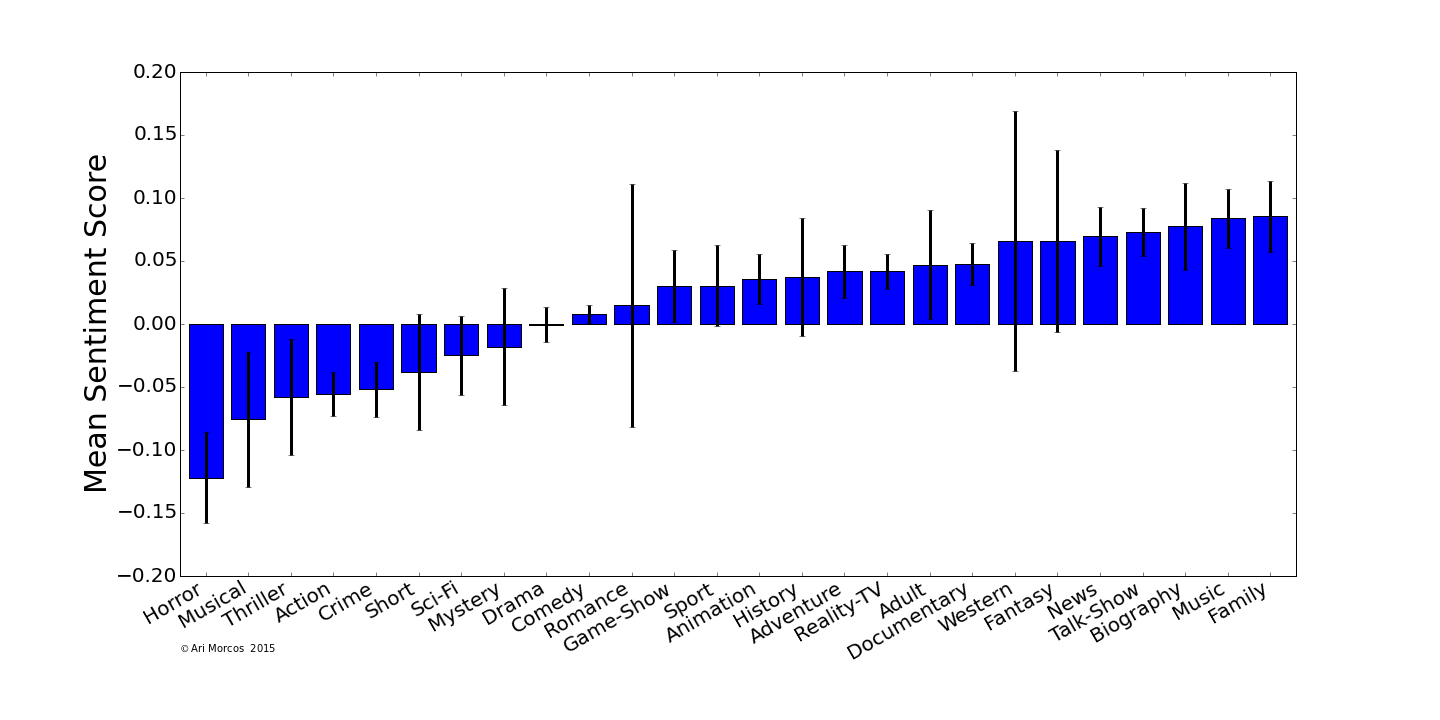

Unfortunately, it seems the answer is no. In fact, it seems they've remained mostly unchanged. The extreme variation between 1950 and 1975 is mostly due to a smaller sample of movies with taglines in the IMDb database for those years. My first thought upon seeing this result was that the multiple meanings problem completely obscured any effect that might be present. As a control for this, I asked how the mean (+/- SEM) sentiment score differs across different film genres.

In general, I think this looks pretty reasonable. Horror, action, thriller, and crime movies are all negative, while family movies are the most positive, and the few genres that seem out of place, like musicals, had few samples. This seems to suggest that the general analysis pipeline works to pull apart the differences between taglines, leading me to believe that the null result above is, in fact, genuine.

On average, movie taglines are neutral or ever so slightly positive and have been that way for the last half-century.

The challenges of sentiment analysis

When I first decided to take on this analysis, I assumed that the sentiment analysis component would be relatively straightforward. While it seems that the results of this analysis are in the right ballpark, the manner in which I dealt with the multiple meanings problem here would be drastically insufficient for say, mining sentiment on Twitter to predict future stock price movements. One way I could have better handled the multiple meanings problem would have been to use n-grams (i.e. groupings of words. A bigram is a pair of words, a trigram a word triplet, etc.). These might have allowed me to better extract the precise meaning of a given word in a tagline given its context. Another, substantially more complex approach, is to use Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) to approach sentiment analysis. RNNs are actively being used for sentiment analysis, often with extremely good results. If I were to continue this analysis, I think this is the approach I would take.

Publication bias

Once I had convinced myself that this analysis produced a negative result, I struggled immensely with whether or not to write about it. The bias against negative results is ubiquitous throughout academia, perhaps especially in the life sciences, and as a product of academia, it's been ingrained in me. I think most would agree, however, that this bias is harmful to the entire scientific endeavor.

On this blog, I intend to publish all my results, whether or not they agree with the most interesting interpretation of the data.

You can check out the iPython notebook used to perform these analyses here.